Whodunnit?

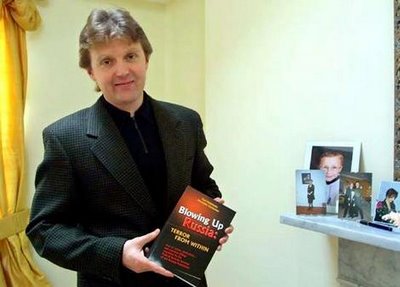

Everyone loves a good game of whodunnit? It's especially fun when the media join in, speculating wildly as they currently are over the sudden death of Arkadi "Badri" Patarkatsishvili, linking it endlessly to Alexander Litvinenko. Never mind that Patarkatsishvili, or "the Georgian" as Jeremy Paxman amusingly had it a couple of hours ago when he failed to pronounce his name, doesn't seem to have any particular grudge against Putin or Russia (Update, slight correction: He had been charged with fraud in Russia and fell out with Putin, but nowhere near on the scale that others have, nor had he been making the kind of accusations against Putin that Litvinenko had) but rather against the Georgian state, which is currently still ruled by the distinctly cool towards Russia Mikheil Saakashvili, it's obviously all inter-linked and highly worrying. We'll know more in the morning, but the police seem to have only described the death as "suspicious" because it is as yet unexplained, not necessarily indicating any foul play. I could be proved horrendously wrong in a few hours, but the media itself ought to remember the general idiocy and assumptions made about Bob Woolmer's death.

In any case, a far more interesting and genuinely worrying case of whodunnit? is currently taking place in Syria. Just a day before the 3rd anniversary of the massive car bombing that killed the ex-prime minister of Lebanon Rafik Hariri, largely blamed on Syria and which forced the exodus of much of Syria's security apparatus from the country, Imad Mughniyeh, accused of masterminding numerous kidnappings and bombings by Hizbullah, has been killed in a similar fashion.

Those instantly leaping to conclusions will be pointing the finger squarely at Mossad, Israel's foreign intelligence service, with perhaps a side-dashing of the CIA. Hizbullah and Iran have both pointedly denounced the attack, directly accusing Israel of being the perpetrator. Israel has denied any involvement in a rather terse release from prime minister Olmert's office, stating "Israel rejects the attempt by terror groups to attribute to it any involvement in this incident. We have nothing further to add," but Israel has a policy of never owning up to strikes on foreign territory.

It's the method that will naturally raise the most suspicions. A car bombing isn't the CIA's style of late; they prefer the Hellfire missile delivered by manless drone, used in both the recent strike that killed Abu Laith al-Libi, although it hasn't been confirmed whether it was the US or Pakistan itself that launched the attack, and the case of the strike which was meant to have targeted al-Zawahiri, and instead killed the depressingly familiar innocents who got in the way. Mossad certainly has used car bombings in the past, but because the nature of the conflict within Israel and the occupied territories, the Hellfire missile has again been the most favoured weapon, although this is technically by the Shin Bet, Israel's internal security agency. The most notable recent assassination not involving an air strike was the killing of Yahya Ayyash, known as the "Engineer", who was killed by a mobile phone rigged with explosives.

Assuming that it was the work of Mossad and not the result of internal bickering within Hizbullah, an attack that went horribly wrong, or the result of a breakdown in the relationship between Mughniyeh and Iran or Syrian operatives, the main problem as always with these assassinations is that they are first and foremost, regardless of whom they target, acts of state terrorism. If the target is missed, innocents are usually the victims, which it turn only exacerbates the hate and mistrust towards the country attempting the assassination in the first place. What then should be the options for dealing with pieces of work such as Mughniyeh? Kidnapping, or as we're now referring to it, rendition, is problematic not just because those recently rendered have been tortured and are now facing manifestly unfair trials, but it also encourages general lawlessness by states the world over. While we haven't been directly involved in most of the rendition cases that have been brought to light, excepting the case of al-Rawi and el-Banna where the CIA did the dirty work of MI5 for them, let's say that at some future point there's a terrorist attack masterminded from abroad and that we kidnap and transfer the accused to stand trial in this country without any involvement in that nation's extradition process. We would be in effect opening Pandora's box, and if you thought that Litvinenko's assassination was unpleasant, wait until you have FSB agents running around kidnapping Russian dissidents and oligarchs with the justification that we've done it to terrorists.

Of course, we can get into arguments of tit for tat. The targets chosen by Mugniyah were mostly what would be considered legitimate targets in times of war, embassies and barracks, excepting the 1994 AMIA bombing, although Hizbullah has never been conclusively linked to that attack, even if it was their usual modus operandi, and the TWA Flight 847 hijacking where a U.S. navy diver was murdered, although the rest of the passengers and crew were released unharmed. None of the events took place during war however, or at least without all the other options for legitimate, peaceful protest and non-violent resistance being exhausted, and innocents were killed. Does however such indiscriminate targeting justify the same in response? We could argue that Mugniyah's death was a targeted killing, although it appears to have killed a passer-by according to reports, but this is no different to when Israel launches Hellfires into Gaza and acts apologetically when innocent Gazans are killed along with the targeted militants. The only acceptable way of bringing Mugniyah to justice would have been, in these circumstances, to kidnap him, but even then could he have received a fair trial in Israel?

We shouldn't forget in all of this that Hamas and Hizbullah continue to hold Gilad Shalit and Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev respectively, and little is known about their current state of health. All should be released immediately. The death of Mugniyah is however also unjustifiable. Quite apart from anything else, violence only breeds more violence, a truism which has never become a cliché, one which the United States, doing everything but celebrating openly his passing, ought to have learned by now. Hizbullah are already threatening revenge, and while a repeat of the 2006 war seems highly unlikely, the very last thing that Lebanon needs, let alone the Middle East as a whole, is more misery, bloodshed and instability.

Labels: Alexander Litvinenko, assassinations, CIA, Hamas, Hizbullah, Imad Mughniyeh, Israel, kidnapping, Mossad, Patarkatsishvili, rendition